Recently I've been thinking a lot about literature inertia and the best ways to accommodate and deal with it. What is literature inertia? It is a phrase that a professor I had at Penn State used to describe the common theme in fields of research where things are done a certain way because that's the way they have always been done. Everyone bases their analysis or technique on one "seminal" paper at some point in the past. The methods in that paper are likely the first methods tried that succeeded, and everyone has used them ever since.

I can see some benefits to literature inertia. For one, it provides a consistent way things are done or a "standard" analysis program that all scientists in the field use. This kind of stability allows long term comparison and inter research group comparability. That's fantastic! Maybe the method isn't exactly ideal, but it is the same everywhere and eliminates some of the variables that would otherwise be present. Inertia of a field also means that the wheel isn't re-invented all of the time, which saves the researcher time and lets them pursue the research, not the methods. But is that best for the advancement of science?

The downsides of literature inertia are just as significant as its advantages though. The original methods or code that become the "standard" is likely one of the first that worked well when the research was in the discovery phase. It is also, by necessity, a bit old. There are likely better methods developed that could produce better results. I also believe that the pressure to use a standard procedure is discouraging exploration. Funding isn't commonly given to explore and test new ways of solving a solved problem! Literature inertia can also bias a field against an idea for decades. There are some sub-disciplines that are considered to be very delicate research areas. Working on these new and poorly understood areas runs the risk of having your career marked early as being a borderline crank. Many reasonable ideas have been floated in these fields, but quickly shot down by those following the inertia. Often these ideas are thrown out with little work done to legitimately check their validity. Likewise, one true crank can make an entire area taboo for all researchers.

So what's the answer to this problem? Well, like so many things in science, it probably lies in the gray area in between. While some stability is needed so that each researcher isn't approaching a problem from completely different directions, there should be less discouragement of exploration. Standards are also temporary. Nothing in research is truly permanent. Standards will become out-dated and need replaced. This process isn't easy, painless, or fun, but necessary if science is to remain current and relevant.

Computer data formats are one example I can think of to illustrate inertia. There are many great formats that will stick around for some time such as JSON, HDF5, NetCDF, etc. Some labs still insist on having their own data format though! This is puzzling because the computer scientists have done a very good job of making a flexible data format that is supported by most major programming and scripting languages. The labs using in-house formats must distribute readers (normally only in one or two languages) or share bulky text files to collaborate with others. Why do these labs insist on their format? Because it is what they have been using for years and they don't want to invest the time and effort to change to a more open format. Inertia, for those groups, is crippling their ability to use more recent tools. That matters because if more tools are available to analyze data and they are easy to use, researchers will find it easier to explore their data.

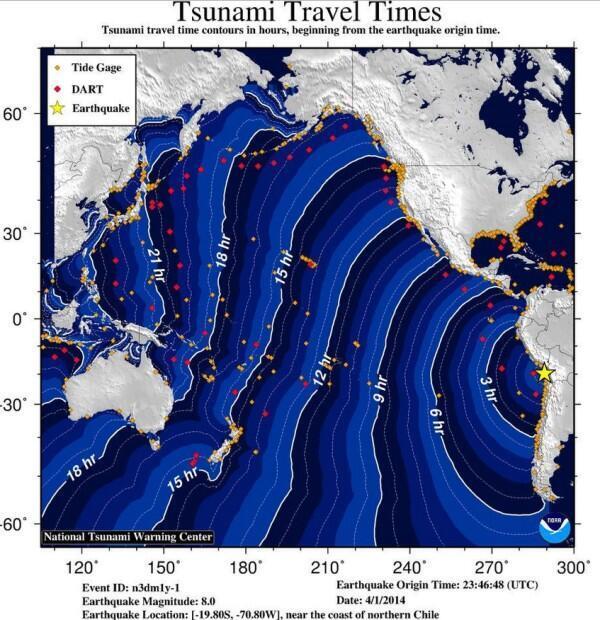

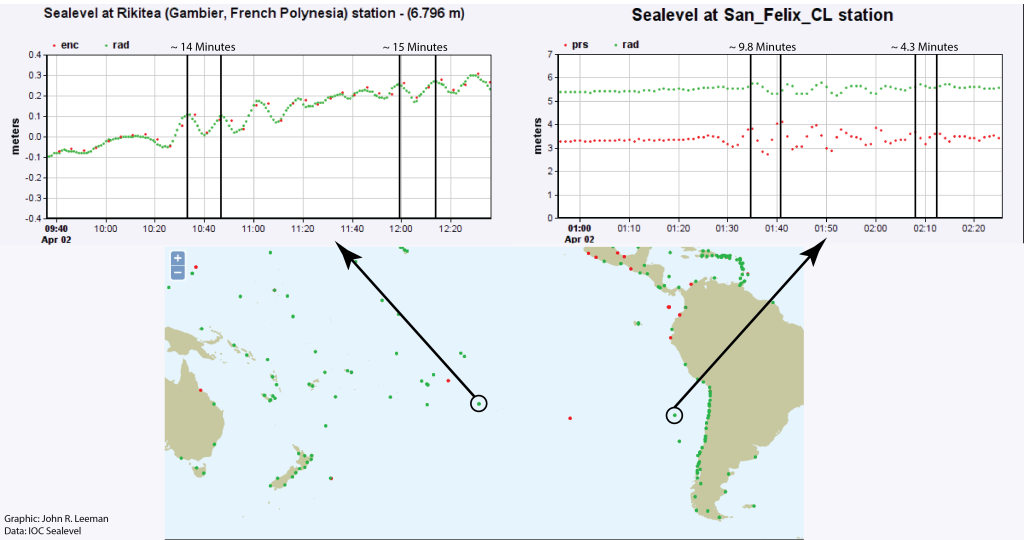

Another example is inversion techniques commonly used to solve for things like earthquake location problems. Some fields are using inversion techniques that came about in the 1950's. These techniques work, in fact, they have been tuned over the years to work very well. For operations on a day to day basis, that stability is important. It is the job of researchers to try new techniques though and explore/improve. Every technique has a weakness, and trying many is important!

I do think that many standard techniques will be challenged with a new group of researchers coming into the job market, but I am concerned about how going against literature inertia could damage long-term job prospects. I've heard well respected traditional faculty say things like "This computer data management problem isn't a decision for you early career people or something you should be involved with." Like wise I've also seen some excellent ideas get pushed out because it isn't the same way things have always been approached. This attitude is likely propagated by the pressure to publish and the damping that puts on free exploration. What do you think?